Introduction

This morning, we are participating in an instructed Eucharist. As we worship together, we will comment on the history and meaning of the liturgy as we know and use it today. Pay attention to the words of the liturgical texts as well as the gestures and ritual you see here today. There is a lesson in every word and every act. As we explore some of them today, may God enlighten our hearts and minds to worship him in spirit and in truth.

For nearly two thousand years, Christians have been gathering together on “the Lord’s Day” (Sunday--the day of the resurrection) to worship and adore the holy Trinity in the liturgy (a Greek word meaning “a work for the people”). Christians have honored the call to continue “in the apostles’ teaching and fellowship, the breaking of Bread, and the Prayers” (Acts 2:42).

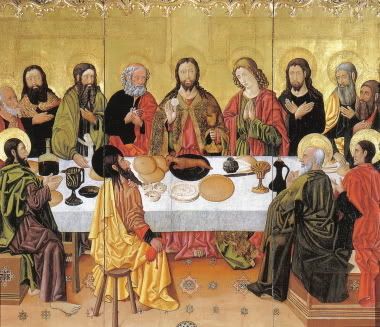

The chief act of worship on this day is the Holy Eucharist, “the sacrament commanded by Christ for the continual remembrance of his life, death, and resurrection, until his coming again.” St. Paul said, “As often as you eat this bread, and drink this cup, you proclaim the Lord’s death till he comes”(1 Cor 11:26). Sacraments (which means “mysteries”) are “outward and visible signs of inward and spiritual grace, given by Christ as sure and certain means by which we receive that grace.” And what is grace? It is “God's favor toward us, unearned and undeserved; by grace God forgives our sins, enlightens our minds, stirs our hearts, and strengthens our wills” (BCP 857-9).

The Holy Eucharist, from the Greek word for thanksgiving, is also called “the Lord's Supper, and Holy Communion; it is also known as the Divine Liturgy, the Mass, and the Great Offering” (BCP 859). It is the summit toward which the activity of the Church is directed, and the fountain from which all her power flows. English priest F. W. Faber, who wrote several hymns in our hymnal, called it the most beautiful thing this side of heaven.

The Holy Eucharist is the meeting place between earth and heaven, where we kneel at God’s altar to adore our Lord Jesus Christ and be nourished with his sacred Body and Blood. The benefits we receive are “the forgiveness of our sins, the strengthening of our union with Christ and one another, and the foretaste of the heavenly banquet which is our nourishment in eternal life.” The Mass is also called a sacrifice because “the Eucharist, the Church's sacrifice of praise and thanksgiving, is the way by which the sacrifice of Christ is made present, and in which he unites us to his one offering of himself” (BCP 859-60).

Before the service begins, the altar must be prepared. In the bible, altars are tables or piles of stone used to offer sacrifice to God. Traditionally, the altar rests in the sanctuary at the eastern end of the church, which is the ancient direction for worship, a symbol of the heavenly Jerusalem. Our Lord likely celebrated his Last Supper at a wooden table, and so altars are often made of wood, symbolizing that table of fellowship and also the cross upon which Christ offered himself to the Father. Since the sixth century, altars have often been made of stone, a symbol of the throne of God, and of Christ--the Rock and Cornerstone of his Church (Eph 2:20). Reflecting the practice of Christians in the ancient Roman catacombs, the relics of saints or martyrs have often been embedded within top of the altar stone (Rev 6:9).

Since we veil things which are precious to us, the altar is often veiled with a frontal in the color of the day. The liturgical colors have a particular symbolism. Green, symbolizing hope and growth is used during most of the Church year. Blue, the color of the Virgin Mary, is used in the season of Advent. White or gold is used during Christmastide, Easter, and other festive occasions. It symbolizes purity and joy. Purple is used in Lent, symbolizing penance and humility. Black is a somber color, sometimes used for times of mourning or requiem Masses. A fair linen cloth, symbolizing the burial shroud of Christ lays across the altar and over the sides. A cross or crucifix traditionally stands on or above the altar, and at least two candlesticks are placed at both ends of the altar, symbolizing Christ as “the light of the world.”

Nearby, on the credence table or shelf (just to the right of this altar) rests the vessels used for worship--including the veiled chalice and paten, the cruets of water and wine, and a bowl and towel used in washing the priest’s hands.

Before the liturgy begins, the clergy put on the liturgical vestments. The first Christians appreciated the significance of wearing special clothing for divine worship. In the earliest days of the Church, they were simply more ornate versions of ordinary clothing. But as fashions changed, liturgical dress remained the same, and was thus distinguished from everyday clothing.

The amice is a square piece of cloth, introduced in the eighth century to cover the neck. The priest places it upon his head, praying, like St. Paul, that God would give him a helmet of salvation to defend him against the assaults of the devil. The alb, form the Latin word alba, or “white,” is the full-length garment symbolizing our baptismal purity, and the robes of righteousness Christ offers us by his grace. It is secured with a rope, or cincture, around the waist. The priest prays that God may likewise gird his passions. The stole is the symbol of the priestly office. It was originally worn over the shoulder, as deacons do so today. The priest wears the stole with both ends hanging down in front, folded in a cross over his heart. Last, the priest puts on the chasuble, from the Latin word casula--”a little house”--named so because of the way it envelops his body.

As we enter the church, it is customary to kneel in silence to prepare our hearts to worship God and to bring our petitions before him. Likewise, the priest prays that he may serve God with a pure mind, and he makes the intention for which he is to offer sacrifice. By longstanding tradition, the Sunday Eucharist is offered pro populum--”for the people” of the parish. The directions of the Greek liturgy, or “Byzantine rite,” specify that the “priest who is about to celebrate the holy Mysteries must have confessed his sins, be reconciled to all people, and have nothing against anyone. He must keep his heart from bad thoughts, be pure, and fast till the time of sacrifice.”

For about four centuries, the ministers have prepared themselves to enter the sanctuary with a confession and the recitation of the 43rd Psalm as a prayer of reverence and confidence in God’s mercy. Verse 4 carries the theme: “that I may go unto the altar of God, to the God of my joy and gladness.”

The Entrance Rite

The Christians continued a Jewish practice of the choir and ministers entering the courts of the temple in procession, accompanied by singing. Many of the psalms were composed and used for this occasion. Consider this portion of Psalm 68 (vv 24-25): “They see your procession, O God, / your procession into the sanctuary, my God and King. / The singers go before, musicians follow after, / in the midst of maidens playing about the hand drums.”

Pilgrims would walk in procession toward holy shrines, singing these psalms. Jesus entered the holy city on Palm Sunday in a triumphant procession. Procession symbolizes our journey through this life, on our way to heaven. We make our journey joyfully, and as St Paul wrote to the Ephesians, we “speak to one another in psalms and hymns and spiritual songs, singing and making melody in your heart to the Lord” (Eph 5:19).

The liturgy begins with an acclamation--a call to praise, bless, and worship the Holy Trinity. The sign of the cross is customarily made by all in remembrance of our baptism. The priest continues with the Collect for Purity, a short prayer asking for purity of heart in the service of God’s sanctuary. This is the last prayer of preparation by the ministers as they enter the church in procession.

A hymn, psalm, or anthem may be sung. The people standing, the Celebrant may say

Blessed + be God: Father, Son, and Holy Spirit.

And blessed be his kingdom, now and for ever. Amen.

The Celebrant says

Almighty God, unto whom all hearts are open, all desires known, and from whom no secrets are hid: Cleanse the thoughts of our hearts by the inspiration of thy Holy Spirit, that we may perfectly love thee, and worthily magnify thy holy Name; through Christ our Lord. Amen.

The Kyrie--”Lord, have mercy upon us”--is the last Greek element in the Latin liturgy. It is preserved in our Prayer Book to this day, and may continue to be sung in its Greek form It is a solemn prayer for God’s mercy. It is used especially during the penitential seasons.

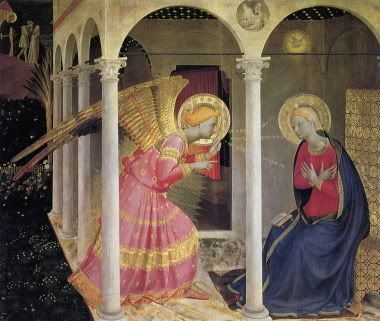

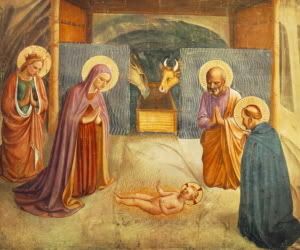

At the birth of Jesus, the angels sang before the shepherds, “Glory to God in the highest, and peace to men on earth.” In AD 112 the governor Pliny reported to the emperor Trajan that the Christians in Bithynia had the custom of meeting together before dawn on an appointed day [Sunday] and they would “sing a hymn to Christ as God.” The form of the hymn of praise Gloria in excelsis deo we sing today at the beginning of the Mass is attributed to Pope Telesphorus, 130 years after the birth of Christ. It is custom to make the sign of the cross at the conclusion of this ancient canticle.

Here is sung or said

Lord, have mercy upon us. (or Kyrie eleison.)

Christ, have mercy upon us. (or Christe eleison.)

Lord have mercy upon us. (or Kyrie eleison.)

When appointed, the following hymn or some other song of praise is sung or said, in addition to, or in place of, the preceding, all standing

Glory be to God on high, and on earth peace, good will towards men. We praise thee, we bless thee, we worship thee, we glorify thee, we give thanks to thee for thy great glory, O Lord God, heavenly King, God the Father Almighty. O Lord, the only-begotten Son, Jesus Christ; O Lord God, Lamb of God, Son of the Father, that takest away the sins of the world, have mercy upon us. Thou that takes away the sins of the world, receive our prayer. Thou that sittest at the right hand of God the Father, have mercy upon us. For thou only art holy; thou only art the Lord; thou only, O Christ, with the Holy Ghost, art most high in the + glory of God the Father. Amen.

A liturgical greeting (“the Lord be with you”) is used throughout the service. It is a common greeting from ancient Israel we see used in the Book of Ruth (2:4). Even today, our common language is filled with religious imagery. “Hello” comes from the word for “praise,” and “goodbye” means “God be with you.”

The Collect of the Day is a prayer unique to each Sunday. It sums up the themes of the occasion in a common prayer to God. It has three parts: an opening praise and description of God, a request, and a closing doxology. The priest faces East and extends his hands in the gesture we call the “orans” position. This ritual is an inheritance from our Jewish ancestors.

The Celebrant says to the people

The Lord be with you.

And with thy spirit.

Let us pray.

The Celebrant says the Collect of the Day, and the People respond ”Amen.”

The Lessons

The people sit. One or two Lessons, as appointed, are read. Silence may follow.

A Psalm, hymn, or anthem may follow each Reading.

Christian worship was born out of the experience of the Jewish synagogue. There, elders and scribes would read from the ancient scrolls and comment on the meaning. This is the origin of our readings and sermon. In the Gospel of Luke, Jesus began his ministry in this way. Returning from the temptations of the wilderness, he went to the synagogue at his home town of Nazareth (Lk 4:16-21). Jesus read a passage from Isaiah. The sermon was very simple; he told them, “Today, in your hearing, this scripture has been fulfilled.”

Passages from the Old Testament continue to be read in Christian circles. They also read from letters of apostles and memoirs of the life of Jesus that were circulating at the time. These became the New Testament. Originally, the response “Thanks be to God” was a signal from the bishop that the reading had gone on long enough. We use it today to affirm our believe in the scriptures as the Word of God, containing “all things necessary for salvation.” St. Paul wrote to Timothy, “All scripture is inspired by God [that is, God-breathed], and is profitable for doctrine, for reproof, for correction, for instruction in righteousness, that the [people] of God may be equipped for every good work” (2 Tim 3:16-17). Therefore, the reading and proclamation of scripture in our worship today is important for us.

When the Gospel is read at the Eucharist, it is read with a sense of celebration and proclamation. We stand in its honor as the message of Jesus is brought into the midst of the people. The candles used to give light for the gospel book also remind us of Jesus, the light of the world, going out into the world to shine in the darkness.

As the deacon begins the reading, it is customary to follow him in tracing the sign of the cross with the thumb over your forehead, lips, and chest. It is our prayer that the words of Jesus may abide in our minds, be spoken by our lips, and fill our hearts with the love of God.

Then, all standing, the Deacon or a Priest reads the Gospel. After the Gospel, the Deacon says

The Gospel of the Lord.

Praise be to thee, O Christ.

The Sermon

The sermon is a vital part of the service, and continues an ancient practice of proclaiming God’s message from the past and applying it to our lives today. The Lord Jesus Christ taught people in public speaking, mostly through parables. His “sermon on the mount” is a beautiful portrait of life in Christ. The early Christians continued the art of preaching. In the Acts of the Apostles, a number of sermons from the early Church are recorded. They proclaimed God’s mighty acts through Israel’s history, his promise of a Messiah and the fulfillment of that promise in Christ Jesus, a testimony of the death and resurrection of Christ, and a call to faith and repentance.

In today’s Gospel reading (Jn 6:60-69), Jesus had shocked his audience with the statement that he is the true bread from heaven and one must eat his sacred Flesh and drink his precious Blood to have eternal life with God. Some of the disciples said, “This is a difficult saying. Who can accept it?” Many of them no longer followed him after that. Jesus turned to the Twelve and asked them, “Do you also wish to go away?” Speaking for the group, Peter said, “Lord, to whom shall we go? You have the words of eternal life; and we have believed, and have come to know, that you are the Holy One of God.”

Sometimes the message that God gives us is difficult to understand or hard to accept, but we can trust that they are truly words of life, for they come from the Author of Life. Our proper response is faith. Since the sixth century in the East, and the eleventh century in the West, the sermon has been followed with the Nicene Creed. It is not a replacement for holy Scripture, but it is a summary of the central truths Scripture teaches us. Thus, the creed is known as the Symbol of Faith, the sign of our Christian belief.

The Creed originated at the ecumenical Council of Nicea in AD 325. Most lines were chosen as to clarify different misunderstandings that arose from conflicting biblical interpretation, especially concerning the relationship of the Father and the Son. The Creed was expanded in 381 at the First Council of Constantinople with the articles addressing the Spirit and the Church. The Creed is used on Sundays and major feast days. It is customary to make the sign of the cross at the end of the Creed.

On Sundays and other Major Feasts there follows, all standing

The Nicene Creed

I believe in one God, the Father Almighty, maker of heaven and earth, and of all things visible and invisible;

And in one Lord Jesus Christ, the only-begotten Son of God, begotten of his Father before all worlds, God of God, Light of Light, very God of very God, begotten, not made, being of one substance with the Father; by whom all things were made; who for us men and for our salvation came down from heaven, and was incarnate by the Holy Ghost of the Virgin Mary, and was made man; and was crucified also for us under Pontius Pilate; he suffered and was buried; and the third day he rose again according to the Scriptures, and ascended into heaven, and sitteth on the right hand of the Father; and he shall come again, with glory, to judge both the quick and the dead;whose kingdom shall have no end.

And I believe in the Holy Ghost the Lord, and Giver of Life, who proceedeth from the Father and the Son; who with the Father and the Son together is worshiped and glorified;

who spake by the Prophets. And I believe one holy Catholic and Apostolic Church; I acknowledge one Baptism for the remission of sins; and I look for the resurrection of the dead, and the life + of the world to come. Amen.

The Prayers of the People

Form I

The Deacon or other leader says

With all our heart and with all our mind, let us pray to the Lord, saying "Lord, have mercy."

For the peace from above, for the loving-kindness of God, and for the salvation of our souls, let us pray to the Lord. Lord, have mercy.

For the peace of the world, for the welfare of the Holy Church of God, and for the unity of all peoples, let us pray to the Lord. Lord, have mercy.

For our Bishop, and for all the clergy and people, let us pray to the Lord. Lord, have mercy.

For our President, for the leaders of the nations, and for all in authority, let us pray to the Lord. Lord, have mercy.

For this city, for every city and community, and for those who live in them, let us pray to the Lord. Lord, have mercy.

For seasonable weather, and for an abundance of the fruits of the earth, let us pray to the Lord.

Lord, have mercy.

For the good earth which God has given us, and for the wisdom and will to conserve it, let us pray to the Lord. Lord, have mercy.

For those who travel on land, on water, or in the air [or through outer space], let us pray to the Lord. Lord, have mercy.

For the aged and infirm, for the widowed and orphans, and for the sick and the suffering, let us pray to the Lord. Lord, have mercy.

For the poor and the oppressed, for the unemployed and the destitute, for prisoners and captives, and for all who remember and care for them, let us pray to the Lord. Lord, have mercy.

For all who have died in the hope of the resurrection, and for + all the departed, let us pray to the Lord. Lord, have mercy.

For deliverance from all danger, violence, oppression, and degradation, let us pray to the Lord. Lord, have mercy.

For the absolution and remission of our sins and offenses, let us pray to the Lord. Lord, have mercy.

That we may end our lives in faith and hope, without suffering and without reproach, let us pray to the Lord. Lord, have mercy.

Defend us, deliver us, and in thy compassion protect us, O Lord, by thy grace. Lord, have mercy.

In the communion of [the ever-blessed Virgin Mary, and of] all the saints, let us commend ourselves, and one another, and all our life, to Christ our God. To thee, O Lord our God.

Silence. The Celebrant adds a concluding Collect.

The Prayers of the Faithful are among the oldest parts of the Mass, but fell soon out of use and were only reintroduced in our liturgy in 1549. In the East, the prayers took the form of a litany. In the West, the prayers included long periods of silence for people to voice their petitions to God. In the history of Anglican Prayer Books, the Prayer for the Whole State of Christ’s Church was sometimes joined to the offering at the Eucharist. It is a time to intercede for others and to bring our own needs to God. We are called to pray for the universal Church, our nation, the welfare of all people, local needs and concerns, for those who suffer in this life or are in danger, and for the faithful departed (BCP 383). It is customary to make the sign of the cross at the mention of the departed, in remembrance that our life belongs to Christ.

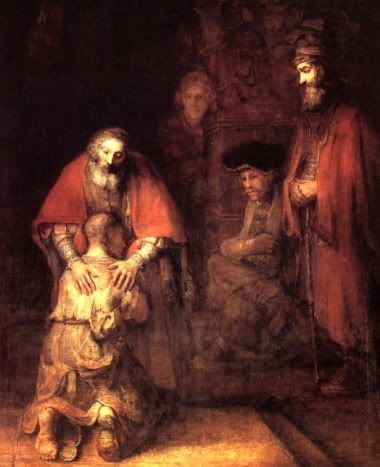

Our mutual prayers are followed by a Confession and Absolution. This rite is a sacramental, a means of grace. The sacrament of reconciliation, by private confession in the presence of a priest, is also available for those seeking forgiveness and healing in their lives. In response to hearing God’s word proclaimed and preached, we are convicted of sin and voice our need for forgiveness. The absolution given by the priest reminds us that our God is loving and merciful. He forgives all the sins of those who come seeking pardon. Repentance means changing our way of life, and the gift of the Holy Spirit empowers us to do so (for all goodness comes from God). The absolution may be followed by some comforting words from Scripture.

Jesus stressed the importance of repentance, humility, and charity in worship, especially since we are called to worship together as a Church. Jesus said, “If you bring your gift to the altar, and there recall that your [neighbor] has something against you, leave your gift there at the altar; go and first be reconciled with your [neighbor], and then come back to offer your gift” (Mt :23-4).

Ss. Peter and Paul urged the people of their flock to “greet one another with a holy kiss” (Rom 16:16; 1 Cor 16:20; 2 Cor 13:12; 1 Th 5:26; 1 Pet 5:14). God’s gift to us is charity and reconciliation. In the medieval English church, a pax board--a plate with an engraving of the Lamb of God, the sacrifice for sin that makes peace with God--was passed around to be reverenced with a holy kiss. After the absolution today, we may stand and offer one another a gesture of the Peace and charity that comes from above.

The Confession of Sin

Let us humbly confess our sins unto Almighty God.

Silence may be kept.

Minister and People

Almighty God, Father of our Lord Jesus Christ, maker of all things, judge of all men: We acknowledge and bewail our manifold sins and wickedness, which we from time to time most grievously have committed, by thought, word, and deed, against thy divine Majesty, provoking most justly thy wrath and indignation against us. We do earnestly repent, and are heartily sorry for these our misdoings; the remembrance of them is grievous unto us, the burden of them is intolerable. Have mercy upon us, have mercy upon us, most merciful Father; for thy Son our Lord Jesus Christ's sake, forgive us all that is past; and grant that we may ever hereafter serve and please thee in newness of life, to the honor and glory of thy Name; through Jesus Christ our Lord. Amen.

The Bishop when present, or the Priest, stands and says

Almighty God, our heavenly Father, who of his great mercy hath promised forgiveness of sins to all those who with hearty repentance and true faith turn unto him, have mercy upon you, pardon + and deliver you from all your sins, confirm and strengthen you in all goodness, and bring you to everlasting life; through Jesus Christ our Lord. Amen.

The Peace

All stand. The Celebrant says to the people

The peace of the Lord be always with you.

And with thy spirit.

Overview of the Holy Communion

This concludes what was once known as the Mass of the Catechumens. Visitors and catechumens--those preparing for holy Baptism--would be dismissed at this time. The Liturgy continued with the Mass of the Faithful. While the first part of the liturgy centers around the word, the second part of the liturgy centers around the altar. The offertory is the part of the service when the offerings of the people are collected and brought to the altar. The vessels and matter for the Holy Communion are also prepared during this time.

The Eucharist is often called our sacrament of unity, and deep symbolism of unity is involved in this part of the liturgy. A manual of Church teaching and practice from the first century, called the Didache (ch 9, 10), had this to say: “As this broken bread was scattered over the hills, and then when gathered, became one, so may your Church be gathered from the ends of the earth into your Kingdom. ... Let no one eat and drink of your Eucharist but those baptized in the name of the Lord. ... To us you have granted spiritual food and drink for eternal life through Jesus Christ our Lord.”

In the Holy Eucharist, Jesus takes, blesses, breaks, and gives. In this act of worship, God takes symbols of humanity--bread and wine--and blesses them to use them as vessels of his Presence. Signs of our humanity become signs of Christ’s divinity. Thus we are united to the Son in his sacrifice, for the Body which is broken and the Blood shed for the forgiveness of sins on the cross are returned to us as a foretaste of the heavenly banquet and a pledge of eternal life.

The Offertory

Only pure bread--made of wheaten flour and water--and pure fermented grape wine may be used in the Eucharist. In the Western Church, following Jewish practice of the Passover and the example of Christ at the Last Supper, the bread is unleavened. Deacons normally prepare the altar at this time. A square linen cloth is spread upon the table. It is called the corporal because the Body of Christ lays upon it. The bread--called a host, from the Latin hostia, meaning a “sacrificial victim”--rests on a plate of precious metal called a paten.

The flat square of stiffened linen which rests upon the chalice is called the pall. It is removed, along with the purificator, the strip of cloth used to wipe the vessels clean. The chalice is filled with wine, and to that is added a little water. This is a practice of temperance inherited from the Jewish tradition of the Passover, where the cup of blessing was the third cup of wine consumed at the supper. St. Justin Martyr confirms that this was the custom in the Church of the second century (1 Apology 65). But the Christians also saw wonderful symbolism in the mixing of water in wine. As the two substances become fully united, it is a reminder of the perfectly harmonious unity of the divine and the human in the one person of Jesus Christ. When the priest blessed the water to be added to the wine, he prays, “O God, who wonderfully created, and yet more wonderfully restored, the dignity of human nature: Grant that through this mingling of water and wine, we may share the divine life of him who humbled himself to share our humanity, your Son Jesus Christ” (BCP 252).

Another ceremony carried over from Jewish worship is the ritual washing of hands. As the celebrant washes his hands, he prays these words from Psalm 26: “I will wash my hands in innocence, O LORD, / that I may go in procession round your altar, / Singing aloud a song of thanksgiving / and recounting all your wondrous deeds.”

The Great Thanksgiving

After the oblations have been prepared, the offerings are brought forward to the altar in procession. It is customary in this place to sing a doxology during the presentation of the offerings, to show it as an act of praise and thanksgiving to God. Then the celebrant faces the people and begins the Great Thanksgiving with a greeting and an exchange exalting God. It is also known by the Latin phrase sursum corda, meaning, “Lift up your hearts.” The priest faces the altar and expands on the praise of God, incorporating the themes of the particular feast or season of the Church year. That concludes with the singing of the Sanctus, meaning “holy.” At this point, we see the altar as the meeting place between heaven and earth. We join our voices with the angels, the faithful departed, and all the hosts of heaven in singing the praises of the Lord.

The first part of this hymn of praise is taken from the Book of Isaiah. In his vision in the temple, the prophet sees angels stationed around the throne of God, singing, “Holy, holy, holy is the Lord God Almighty. The whole earth is filled with his glory” (Is 6:3). The second part of that hymn anticipates the arrival of Jesus in the eucharistic bread and wine. We welcome him in the words of the multitude that hailed Jesus at his triumphal entry into Jerusalem on Palm Sunday: “Hosanna to the Son of David. Blessed is he that comes in the Name of the Lord. Hosanna in the highest” (Mt 21:9).

The ringing of bells frequently punctuate this part of the liturgy. This practice comes from the medieval period in the West when many of these prayers were recited in a low voice out of reverence and awe. Bells let the people who are too far away to hear know what part of the liturgy is being recited at the altar. It is customary to make the sign of the cross at the word “blessed,” for we also come to this place in the Name of the Lord.

During the Offertory, a hymn, psalm, or anthem may be sung.

Representatives of the congregation bring the people’s offerings of bread and wine, and money or other gifts, to the deacon or celebrant. The people stand while the offerings are presented and placed on the Altar.

Eucharistic Prayer II

The people remain standing. The Celebrant, whether bishop or priest, faces them and sings or says

The Lord be with you.

And with thy spirit.

Lift up your hearts.

We lift them up unto the Lord.

Let us give thanks unto our Lord God.

It is meet and right so to do.

Then, facing the Holy Table, the Celebrant proceeds

It is very meet, right, and our bounden duty, that we should at all times, and in all places, give thanks unto thee, O Lord, holy Father, almighty, everlasting God. . . . Therefore with Angels and Archangels, and with all the company of heaven, we laud and magnify thy glorious Name; evermore praising thee, and saying,

Holy, holy, holy, Lord God of Hosts:

Heaven and earth are full of thy glory.

Glory be to thee, O Lord Most High.

Blessed + is he that cometh in the name of the Lord.

Hosanna in the highest.

The people kneel or stand.

We kneel in reverence for the eucharistic prayer, also called the canon, a Greek word meaning “standard,” or “rule of measure.” The priest voices our praise and thanks to God the Father for his act of creation, and for his saving acts through history, most especially the gift of his Son Jesus Christ, who reconciled the world to God, “making peace by the blood of his cross” (Col 1:20). Jesus Christ freely gave himself to the Father as an atonement for our sins, and he bade us to continue this memorial of his passion. And so the priest, as Jesus did at the Last Supper, takes bread and wine, and speaks those words of Christ, “This is my Body,” and, “This is my Blood.”

Consecration means to “set apart.” Common elements of bread and wine are set apart for divine use. Jesus uses them to share with us the gift of himself. The priest raises up the Body and Blood of the Lord so the faithful may look upon them and adore the risen Lord. In this spirit, many people follow the custom of making the sign of the cross and privately praying the words of “doubting” Thomas, who, when he had faith in the risen Lord, said to Jesus, “My Lord, and my God!” (Jn 20:28).

The priest continues the prayer of thanksgiving, asking not only that the Holy Spirit bless the eucharistic bread and wine, but also that the Spirit may bless and change us and join the gift of ourselves to Jesus’ perfect offering to the Father. At the conclusion of the eucharistic prayer, our offering made in remembrance of the death, resurrection and return of the Lord Jesus is brought together into one act of praise to God. This is the worship of heaven, as St. John shows us in the Book of Revelation: “I heard every creature in heaven and on earth and under the earth and in the sea, everything in the universe cry out, ‘To the One who sits on the throne, and to the Lamb, be blessing and honor, glory and might, forever and ever’”(Rev 5:13).

Then the Celebrant continues

All glory be to thee, O Lord our God, for that thou didst create heaven and earth, and didst make us in thine own image; and, of thy tender mercy, didst give thine only Son Jesus Christ to take our nature upon him, and to suffer death upon the cross for our redemption. He made there a full and perfect sacrifice for the whole world; and did institute, and in his holy Gospel command us to continue, a perpetual memory of that his precious death and sacrifice, until his coming again.

At the following words concerning the bread, the Celebrant is to hold it, or lay a hand upon it; and at the words concerning the cup, to hold or place a hand upon the cup and any other vessel containing wine to be consecrated.

For in the night in which he was betrayed, he took bread; and when he had given thanks to thee, he broke it, and gave it to his disciples, saying, "Take, eat, this is my Body, which is given for you. Do this in remembrance of me."

Likewise, after supper, he took the cup; and when he had given thanks, he gave it to them, saying, "Drink this, all of you; for this is my Blood of the New Covenant, which is shed for you, and for many, for the remission of sins. Do this, as oft as ye shall drink it, in remembrance of me."

Wherefore, O Lord and heavenly Father, we thy people do celebrate and make, with these thy holy gifts which we now offer unto thee, the memorial thy Son hath commanded us to make; having in remembrance his blessed passion and precious death, his mighty resurrection and glorious ascension; and looking for his coming again with power and great glory.

And we most humbly beseech thee, O merciful Father, to hear us, and, with thy Word and Holy Spirit, to bless and sanctify these gifts of bread and wine, that they may be unto us the Body and Blood of thy dearly-beloved Son Jesus Christ.

And we earnestly desire thy fatherly goodness to accept this our sacrifice of praise and thanksgiving, whereby we offer and present unto thee, O Lord, our selves, our souls and bodies. Grant, we beseech thee, that all who partake of this Holy Communion may worthily receive the most precious Body and Blood of thy Son Jesus Christ, and be filled with thy grace and heavenly benediction; and also that we and all thy whole Church may be made one body with him, that he may dwell in us, and we in him; through the same Jesus Christ our Lord; By whom, and with whom, and in whom, in the unity of the Holy Ghost all honor and glory be unto thee, O Father Almighty, world without end. AMEN.

And now, as our Savior Christ hath taught us, we are bold to say,

Our Father, who art in heaven, hallowed be thy Name, thy kingdom come, thy will be done, on earth as it is in heaven. Give us this day our daily bread. And forgive us our trespasses,

as we forgive those who trespass against us. And lead us not into temptation, but deliver us from evil. For thine is the kingdom, and the power, and the glory, for ever and ever. Amen.

Prayer is work, and prayer can be difficult. Where do we begin? What do we say? St. John the Baptist had instructed his followers how to pray, so the disciples of Jesus asked him how they ought to pray. So Jesus gave us the example we call “the Lord’s Prayer” (Mt 6:9-13; Lk 11:2-4). It has been used in Christian worship since that time as a constant reminder of how we should pray, and thus it is used in all the liturgies of the Book of Common Prayer. Jesus taught us to turn to God as our heavenly Father, asking him to help us praise the Lord and to do his will, to provide for our needs, to forgive our sins, and to save us from evil.

In Latin rite, the priest expanded on this last petition with these words, “Deliver us, O Lord, from every evil--past, present, and future--and mercifully grant us peace in our day with the help of the blessed and glorious ever-virgin Mary, of your blessed apostles Peter and Paul, blessed Andrew, and all your saints; that, through the aid of your mercy, we may always be free from sin, and safe from every danger.” In Greek, or Byzantine rite, the familiar doxology we use was added to the end of the prayer. It is a way of endorsing the sentiments of the beautiful prayer Jesus taught us.

The Breaking of the Bread

The Celebrant breaks the consecrated Bread. A period of silence is kept.

Following Christ’s example at the Last Supper, the priest breaks the bread, a sign of Jesus’ Body, broken on the altar of the cross. The peace may be exchanged here, if it has not been done earlier (BCP 407). The priest breaks off a small fragment of the Host and places it in the chalice, praying silently that this mingling of the Body and Blood of Christ may lead us to everlasting life. It may be followed by the words of St. Paul from 1 Corinthians 5:7 identifying Jesus as our Passover and the holy Eucharist as our own feast of deliverance from evil and death.

Or, an anthem may follow the fraction of the sacred Host. This is usually the Agnus Dei, a hymn composed of the words of St. John the Baptist, who saw Jesus coming to be baptized, and said, “Behold, the Lamb of God that takes away the sins of the world”(Jn 1:29). The hymn and prayer for God’s mercy was added to the liturgy by Pope Sergius I in the seventh century. A prayer we call the “prayer of humble access” may also be said, asking God to grant us grace and humility in approaching the communion rail to receive this most blessed Sacrament. The prayer was added by Archbishop Thomas Cranmer of Canterbury in 1549.

The following or some other suitable anthem may be sung or said here

O Lamb of God, that takest away the sins of the world,

have mercy upon us.

O Lamb of God, that takest away the sins of the world,

have mercy upon us.

O Lamb of God, that takest away the sins of the world,

grant us thy peace.

The following prayer may be said. The People may join in saying this prayer.

We do not presume to come to this thy Table, O merciful Lord, trusting in our own righteousness, but in thy manifold and great mercies. We are not worthy so much as to gather up the crumbs under thy Table. But thou art the same Lord whose property is always to have mercy. Grant us therefore, gracious Lord, so to eat the flesh of thy dear Son Jesus Christ, and to drink his blood, that we may evermore dwell in him, and he in us. Amen.

Facing the people, the Celebrant may say the following Invitation

The Gifts of God for the People of God. [Take them in remembrance that Christ died for you, and feed on him in your hearts by faith, with thanksgiving.]

The ministers receive the Sacrament in both kinds, and then immediately deliver it to the people.

This invitation was adapted from the Greek Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom, which has the invitation, “Holy things for the holy.” The holy Gifts are the Body and Blood of Christ, to nourish those baptized into his death and resurrection. We receive them joyfully because it is only united with Christ that we can share eternal life (Jn 6:53-56). It is our custom to kneel at the altar rail, if you are able to receive communion. Ladies are asked to blot their lipstick before coming forward. The Host is placed on the palm of your right hand or directly on your tongue. It is not irreverent to touch the chalice; in fact, it is very helpful in avoiding spills. Please guide the chalice by the base to your lips in order to receive the precious Blood. Our bishop has given permission for those who desire to receive the Body and Blood together by intinction, for those who desire it. To do so, leave the Host in the palm of your hand. The person serving the chalice will take it, dip it into the chalice, and place it in your open mouth.

For those not able to come forward, please notify an usher if you need Holy Communion brought to you in your pew. If you do not wish to receive Holy Communion at this service, you may instead come forward to receive a blessing. Please cross your arms over your chest to indicate to the priest that you would like a blessing.

What is required of us to receive Holy Communion? St. Paul says, “A person should first examine himself before he eats the bread and drinks the cup. For anyone who eats and drinks without discerning the Body, eats and drinks judgment upon himself”(1 Cor 11:28-29). The Prayer Book adds that, for those receiving Holy Communion, “It is required that we should examine our lives, repent of our sins, and be in love and charity with all people”(BCP 860). Those who are not Episcopalians may also receive Communion in an Episcopal Church. If you are a baptized Christian, who shares our faith in the Presence of Christ in his blessed Sacrament and regularly receive Communion in your own church, you are welcome to do so here today.

God’s love and mercy are available to all. God calls us to his throne to share our lives with him and let him share his life with us. Everything is prepared for the feast of the Kingdom. In the words of Jesus, “Come you blessed of my Father, and inherit the Kingdom prepared for you from the foundation of the world”(Mt 25:34).

During the ministration of Communion, hymns, psalms, or anthems may

be sung. After Communion, the Celebrant says

Let us pray.

Almighty and everliving God, we most heartily thank thee for that thou dost feed us, in these holy mysteries, with the spiritual food of the most precious Body and Blood of thy Son our Savior Jesus Christ; and dost assure us thereby of thy favor and goodness towards us; and that we are very members incorporate in the mystical body of thy Son, the blessed company of all faithful people; and are also heirs, through hope, of thy everlasting kingdom. And we humbly beseech thee, O heavenly Father, so to assist us with thy grace, that we may continue in that holy fellowship, and do all such good works as thou hast prepared for us to walk in; through Jesus Christ our Lord, to whom with thee and the Holy Ghost, be all honor and glory, world without end. Amen.

The Bishop when present, or the Priest, gives the blessing

The peace of God, which passeth all understanding, keep your hearts and minds in the knowledge and love of God, and of his Son Jesus Christ our Lord; and the blessing + of God Almighty, the Father, the Son, and the Holy Ghost, be amongst you, and remain with you always. Amen.

The Deacon, or the Celebrant, may dismiss the people with these words

Let us go forth in the name of Christ.

Thanks be to God.

The liturgy may be over, but the true “work of the people” has just begun. The Lord has nourished us with himself, empowered us with his Spirit, and dimissed us with his blessing. In fact, the word “Mass” comes from the Latin "missio," which is the dismissal. With this word, a Roman judge would dismiss the innocent, or a centurion would sent away his soldiers on a mission. We receive our mission from Christ, who dismisses us with his grace that we may go into the world, grow in discipleship, and become disciples who share the love of God, making other disciples of our Lord Jesus Christ.