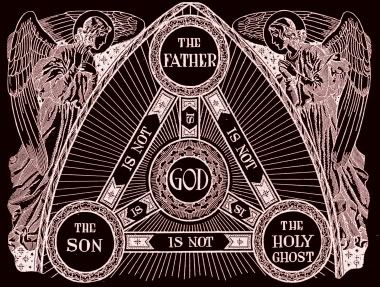

On this Corpus Christi day, here's a paper from my seminary days.Christian worship is the living expression of the spiritual piety and doctrinal belief of its adherents--both in the present and in the past. Since the religion of the disciples of Jesus is characterized by eschatological overtones, it is natural that there are deeply rooted eschatological characteristics to Christian worship as well. Looking toward the consummation of God’s kingdom is the dominant context for worshiping as a part of that kingdom. It is worship in spirit and in truth. As such, it is a prayerful anticipation of, and spiritual participation in, the beatific vision of God.

Eschatology concerns the study of last things in Catholic theology. It covers death, final judgment, heaven, hell, and so forth. However, in the liturgy, the dominant eschatological theme is the final realization of the kingdom of God. This theme is embedded in the origin and theology of Christian eucharistic worship. We can also see eschatological elements develop over time in the manner in which the worshiping community performs its liturgy. We shall look at possible reasons for development in the eschatological shape of eucharistic worship, considering the present state of affairs and possible future developments.

The Supper of the Lord: Covenant Sacrifice and Kingdom FeastThe Lord’s Supper was established by Jesus Christ as a memorial of his passion, the significance and meaning of which includes his incarnation, life, death, resurrection, ascension, and his

parousia or

eschaton (his “coming again in glory”). The word

parousia means appearance, presence, or arrival. It is the natural fulfillment of the redemptive work of Christ, who the Scriptures call both the Alpha and the Omega—the “beginning and the end.”

Salvation history is a chronicle of the redemption, and as such is also the chronicle of a new covenant, which Jesus calls a “covenant in my blood,” that heralds the kingdom of God. Every covenant is established through the act of sacrifice, and Jesus offers sacrifice beginning in a meal with his disciples to inaugurates this covenant.

John’s gospel presents a vivid picture of the sacrificial inauguration of the covenant. The Passover is the sacrifice and memorial meal representing the old covenant. Jesus has come to establish God’s kingdom with a new covenant. His memorial meal ushers in the hour of his glorification. In a parallel action, Jesus is slain along with the sacrificial Passover lambs so that he is truly

“the Lamb of God that takes away the sins of the world.” The lambs are slain to forgive sin, for according to the Law,

“without the shedding of blood, there is no forgiveness of sin.” Yet the sacrifices of these animals are but a type of the sacrifice of the true Lamb of God. Jesus came not to abolish the law, but to fulfill the law.

In examining the inauguration of a new covenant through the sacrifice of Jesus, we must consider questions like, What was offered? by whom? to whom? when? and why? In the act of sacrifice, there are two main actions—the oblation and the immolation. The oblation is an offering by a priest of gifts to God as a sign of God’s supreme dominion and our dependence upon him. This is often accompanied by some thanksgiving or petition (

e.g. for the remission of sins) with the hope that as the gift is pleasing to God, so he may be moved to grant the petition. The immolation is the conclusion or consummation of the act of sacrifice. The gift which has been given to God is now destroyed or in some way rendered incapable of performing it’s normal function. For example, an animal offered would be killed so that it is no longer a living animal, or a cup of wine would be poured out or grain burned so that it could no longer be consumed. In the sacrifice of the new covenant, Jesus is himself both the Priest and the Victim—the one who offers and that which is offered.

From Anticipation to RealizationThe sacrificial meal is the realization of the sacrificial petition. In the case of the Christian community, this feast is the memorial of the redemptive work and person of Jesus Christ and it is therefore the realization or actualization of the Kingdom established by the new covenant sacrifice. At his Last Supper, Jesus prays for the realization of the Kingdom, as is also reflected in the

Didache:

“As this piece was scattered over the hills and then was brought together and made one, so let your Church be brought together from the ends of the earth into your Kingdom.” Jesus commands his disciples to love one another and joins his priestly petition for their unity in the Spirit with the offering of himself. He takes signs of human life and labor to become his own life and labor. Jesus offers them in thanksgiving to the Father and gives them back to the disciples as tokens of the transformation realized through the new covenant sacrifice of his broken Body and shed Blood. At this point Jesus has offered himself—body, soul, and divinity—to the Father. After his oblation, Jesus is willingly taken into custody of those who would destroy him. The next day he is slain as a Paschal Lamb and this act of immolation concludes the sacrifice in which his Body is broken and his Blood poured out for the life of the world.

In the early Christian communities, the people gathered on the Lord’s Day to participate in the sacrificial meal that was performed after the example of the Last Supper in fulfillment of Jesus’ command,

“Do this as my memorial.” The difference for them is that the oblation of the meal occurs

after Christ has been immolated on the cross. In the spirituality of the Eucharist, therefore, the believer tends to work backwards. In the meal, he or she is to receive the resurrected life of Jesus. Therefore, in thanksgiving the believer retreats in time to the self-offering that Jesus made before his passion. The believer offers him or herself along with Christ, whose passion is commemorated in thanks and praise for the life granted on the far side of the cross. Although Jesus’ work on Calvary is an event at a moment in time, through this Eucharistic memorial, it takes on an eternal character.

Worship in the kingdom is a participation in the work of redemption through praise and thanksgiving. St. Paul urged his readers to

“present your bodies a living and holy sacrifice, acceptable to God, which is your spiritual worship.” The believer offers him or herself with Christ, who in bread and wine took signs of human life and labor and incorporated them into the gift of himself. What was at the Last Supper a banquet of

anticipation is now a communal feast of

realization. In the post-resurrection community, the sacrifice and feast take on an almost cause-and-effect relationship: “Christ our Passover has been sacrificed. Let us therefore celebrate the feast.” It is by participating in the eucharistic banquet that we “proclaim the Lord’s death until he comes” and thereby participate in the kingdom he established.

The Shape of the Sacrificial BanquetEarly in the history of Christian worship, the liturgy was increasingly taken to be an icon of heavenly worship. We see Eucharistic overtones in the picture of the marriage banquet of Christ and his Church at the end of history in the Revelation of St. John. Debate continues over which was the initial influence—whether practice shaped the description or whether the description was more influential in shaping practice. But the conclusion is unavoidable that the liturgy increasingly was characterized as the earthly image of heavenly worship.

The legalization of Christianity in the empire during the fourth century and it’s resultant adoption of official and public trappings—such as the features of court ceremonial—undoubtedly influenced Christian architecture and worship. But was this influence dominant, or were the developments of this period more internally driven as the religion was now free to express itself in the open and evolve unfettered? It is likely that the eschatological shape of the liturgy itself had a deeper and more abiding influence on the eschatological shape of sacred space in Christian art and worship.

By the ritual high-water mark in East and West during the Middle Ages, the heavenly beauty and sublime nature of Christian worship was taken to be one of its most important attributes. Before the conversion of Russia, Duke Vladimir—unsure of which faith to follow—sent emissaries to visit the various churches of Europe. Reporting on their experience at the

Ecclesia Hagia Sophia, the mother church of the East in Constantinople, they said,

“We did not know whether we were in heaven or on earth. It would be impossible to find on earth any splendor greater than this . . . Never shall we be able to forget such beauty.” Later on, Fredrick Faber—an English priest of the 19th Century—similarly became famous for his impression of the Latin Mass as

“the most beautiful thing this side of heaven.”The seasons of the Church year and the development of the rites of Easter and Holy Week are examples of increased eschatological features of Christian worship. Obviously, the season of Advent and the feasts of Ascension, Pentecost, All Saints, and Christ the King are relevant to this development. However, our main concern in this treatment is the standard weekly celebration. The most significant and earliest development is Sunday worship.

In the New Testament period, the Church gathered on “the Lord’s Day” which is the first day of the week. Worship was held on this day as it had been the day of the Lord’s resurrection from the dead and also the day of his subsequent appearances to the disciples. The Lord’s Day is also the “eighth day” of the week—the day on which the new creation begins. The Epistle of Barnabas, dated around the latter New Testament period, ascribes this significance to the institution of the Lord’s Day even before the importance of the resurrection, saying,

“I will make a beginning of the eighth day, that is, a beginning of another world. For that reason, also, we keep the eighth day with joyfulness, the day also on which Jesus rose again from the dead.”Therefore the Lord’s Day signifies both the day of Jesus’ resurrection and the dawning of the new heaven and new earth described by St. John in his Book of Revelation. The precedent of the eighth day as the day of the redemption and the new creation is shown in the development during the second century of celebrating Easter—the Christian Pasch—on a Sunday each year rather than on the particular day corresponding to the 14th of Nisan, when the Jews celebrated the Passover.

The eschatological shape of the Eucharistic rite guided the development of two more significant features—the setting of the holy Mysteries and the characteristics of the minister celebrating them. The celebrant of the holy mysteries was increasingly seen as sharing in the mediating priestly ministry of Christ. This is natural since the minister both stands in the place of Christ in celebrating the Eucharist, as Jesus did with his apostles, and he also prays to God from the assembly in the name of all present. This is why his priestly prayers in the liturgy are always first-person-plural.

Thus, the minister himself took on more of the priestly attributes we see in Christ. He, more than anyone else in the community, is the visible sign or icon of the kingdom. The most obvious form of this early development is the tradition of priestly sexual continence. Celibacy in the New Testament is a sign of the kingdom of heaven where God’s people

“neither marry, nor are given in marriage.” In his ministry, Jesus spoke of this great mystery to those who are called, saying,

“there are also those who have made themselves eunuchs for the sake of the kingdom of heaven. He who is able to accept this, let him accept it.”Many of the first disciples of Jesus (as far as can be known) were married. Some of the early Church Fathers relate to us the tradition that upon entering their ministry, the apostles set aside their wives for the sake of the kingdom. While they did not at all abandon their wives, the discipline was that they were to live as siblings in regards to sexual relations rather than as husband and wife. This practice, they say, continued in the appointing of elders and deacons in churches. Since they needed seasoned men with whom to entrust this ministry, they often had to pick from married men. This practice is reflected in the later New Testament letters. The first major breakdown of this ideal was that some clerics viewed the process as an annulment and a reversion to bachelorhood. As a result, they saw themselves as free to contract (another) marriage. The abuse is addressed with the admonishment that they are only permitted to be the

“husband of one wife.”In the Eastern Church, the discipline developed in a more relaxed form as a matter of practicality. It was most common for the typical parish priest to be married. The practice became standard that married men could be ordained, yet the charism of celibacy for the sake of the kingdom continued to be highly esteemed, and the episcopate became reserved to celibate candidates. While the East (with its emphasis on mystery and symbol) saw the minister as representing the kingdom, the West (with its legalistic perspective) saw the ideal of the kingdom as a discipline to be enforced.

In the West, the ideal of celibacy as refraining from contacting marriage and thus from exercising the rights of marriage was interpreted more strictly. The Synod of Elvira was the first to issue canons relating to what was considered to be the norm of clerical continence. However, strict enforcement of this discipline was not firmly established until the reforms of Pope Gregory VII (and even after, lapses of the rule were not unknown and such marriages were held not only unlawful but also invalid by the First Lateran Council in 1123).

But in both East and West, the Church viewed the minister at the altar as an icon of priestly purity. His continence was an image of participation in the realized life of the kingdom. He functionally continued the Levitical tradition of abstaining from the rights of marriage before times of priestly service. But ontologically, he was a symbol of the higher calling of total continence, exercised by Christ the high Priest—the unique source and irreplaceable model of his own priesthood. Similar to the monastic vocation, the parish priest was a living witness to the Kingdom realized in humanity.

The Procession to ParadiseThe priest guides the eschatological shape of the celebration by its performance. He leads the procession toward the sanctuary of heaven. Salvation history is recounted in the hymns and readings, the work of Christ is proclaimed, the Gospel of the Kingdom is preached, the people make their prayers and offerings, and the priest takes them into the sanctuary to make the offering as the great high Priest, Jesus Christ has entered into the sanctuary of heaven to make the perfect oblation.

So contextualized, the orientation of the church building in which the liturgy is performed “expresses the hope and confidence of the Church in him whose coming was from the East in the historic past, and will be again at the glorious Parousia”—the Eucharist as efficacious memorial of the one, and anticipation of the other, joining the two in the present.

The liturgical action as a whole carried with it a kind of movement led by the priest. This motion was always toward God (

e.g. “Let us attend to the Lord,” “Let us turn to the East,” “Lift up your hearts,” etc.). German liturgist Klaus Gamber noted:

"When the faithful increasingly moved into the center nave, they resembled an army formation, and a certain dynamism was created, something like the procession of the people of God through the desert towards the Promised Land. Facing East was to indicate the direction in which the procession was to move: towards paradise, which had been lost and was to be found again in the East. The celebrant and his assistants were at the head of this procession." The development of iconography and other Church art can rightly be seen as a continuation of the process of making the appearance of earthly worship more akin to the heavenly worship described in the Bible. The sanctuary is separated from the nave (and chancel) by some kind of barrier representing the veil of heaven and marking it off as sacred space. In the East, this developed into the iconostasis that contained, as it were, iconic "windows" into the heavenly sanctuary. In the West, the reredos came to fulfill the role of showing the heavenly character of the sanctuary. Prior to a cross or some image of the crucifixion, the earliest churches had an image of the risen Christ (often depicted as the ruler and lawgiver) in the apse above and behind the altar at the eastern end of the church. The priest stood before the altar and faced this image when offering sacrifice.

This practice enacted the apostolic tradition of watching for the Lord’s return. John of Damascus explains:

"When ascending into heaven, he rose towards the East, and that is how the apostles adored him, and he will return just as they saw him ascend into heaven . . . Waiting for him, we adore him facing East. This is an unrecorded tradition passed down to us from the apostles." Worship as the Icon of Heaven With the delayed

parousia, there is a shift in theological discourse from an

immanent eschatology to a

realized eschatology. Christ’s rule and the life of his Kingdom comes to be seen more as something to partake in now than something to simply be anticipated.

This trajectory is paralleled in Christian worship which increasingly saw the earthly liturgy as a model of, and then as a participation in, the worship of heaven. Though development occurs, it is not so much a change of doctrine as it is a change of perspective. The transition is evident even in the New Testament period and reaches a climax in the late Middle Ages when the Church viewed itself as coterminous with the Kingdom of God and the society called Christendom as having reached a perfect equilibrium.

Joachim of Fiore even theorized that from 1260 this situation would bring about a perfect third age (the Age of the Spirit), where the ideal of the kingdom of heaven is realized on earth.

To assist at the Eucharistic liturgy of the Church is to participate—more clearly than at any other time or in any other way—in the life of the Kingdom. The growth in ritual and ceremonial toward the high Middle Ages (the adoption of the

sanctus, incense and torches, processions, icons and other church art, the extended division of the sanctuary from the nave, the veiling of the canopy and altar, the silence of the canon,

etc.) represent a move toward a liturgy of realized eschatology. It is a worship that brings the

parousia to the hear-and-now.

Ironically, the shift toward our present state of affairs most likely occurs at the high-water mark of ornate ceremonial—the high Middle Ages. When ceremonial is at its height, liturgical worship begins to be more heavenly spectacle than a sharing in heavenly life. The worship of clergy and laity become parallel (rather than integrated) actions. To assist at Mass comes to mean witnessing the elevation rather than praying the liturgy. At this point, liturgical performance almost becomes entertainment—a thing to witness and enjoy. Liturgy is something that appeals to tastes: in music, in architecture, in art and craftsmanship. The focus of the liturgy began an extended shift from a vertical shape (concerned with things of above) toward a horizontal shape (concerned with the here-and-now). In the Baroque period, going to the High Mass was equivalent to going to the opera (an institution which had developed outside the Church, but deeply affected Church life and worship).

The Current State of AffairsOur modern state of affairs is probably not related so much to a return to an immanent eschatology like the early Church as it is to simply the dawning of a post-realized eschatology. Our age has an eschatology without the

eschaton. We are a people who for the most part no longer watch for the Lord’s coming, and now that hope hardly even crosses our minds. Our society is too concerned with the present to give much consideration to the past or the future. This is simply the by-product of the secularization of Western civilization. In cultures where Christianity is relatively new, we find features of the immanent eschatology in worship that characterized the early Church.

The shift in liturgy towards the Baroque period was from participation to pageantry. Even the revival of ritualism in the Romantic Period was probably not a renewal of the eschatological shape of Christian worship. As a reaction to secularization, it was a liturgy that focused on the kingdom, but it was deficient in moving too far from a biblical theological perspective. Rather than a worship that looked toward the glorious

parousia in the future, it looked longingly back to the Medieval "Age of the Spirit," when the kingdom had existed on earth.

A need was felt in many Church circles to return to more simple worship in which the laity can be actively involved. The shift from partaking in heavenly life toward witnessing heavenly spectacle occurred because of an alienation of the laity from an active role in liturgical worship. Since that time, the struggle has been to regain an earlier approach to participation in the liturgy. The Liturgical Movement—whose legitimate concerns were foreshadowed by the radical actions of the Protestant Reformers—has come a long way toward re-integrating the laity and clergy into the one liturgical life of the Church.

The challenge has been to rebuild a sense of community. But the community cannot be left to itself; it must be given direction. The danger of the Liturgical Movement is that the pendulum could swing too far from a biblical perspective. If concern about gathering the people is devoid of it’s purpose of looking toward the advent of God’s kingdom, it looses its vertical shape. To complete renewal, the liturgy should form the people of God not just into a community, but into an eschatological community—a procession that moves in joyful anticipation toward the coming of the Lord.

If we are to return to a liturgy with a dominant eschatological shape, the biggest obstacle to overcome is our ingrained secularized perspective. Often the greatest challenge of believers in our age is to “lift up your hearts.” Change may come, but it cannot come until we turn our gaze back to the East and say with the psalmist:

I lift up my eyes to the hills—from where will my help come?My help comes from the Lord, who made heaven and earth.