Perhaps you had a similar experience . . . in my dormroom and first apartment after leaving home, there were a few things on the walls (some posters and such), but no pictures of family and friends. And now, somehow, my house is full of pictures and memorabilia which serve as a constant visual reminder of those I know and love.

There has always been a puritan element in the Christian tradition. In the early Church, both Tertullian and Clement of Alexandria were outspoken in their view that the prohibition on images in the Decalogue was binding on Christians in every way. To them, images and statues of hereos and gods, with candles and incense burning before them, belonged to the world of paganism—that grip of superstition which they had labored so long to break. Indeed, the only second century Christians known to fully use images of Christ were the radical Gnostics who followed the licentious Carpocrates.

Yet, it is natural that ordinary believers who comprehend the world through the eyes and ears would not only want to hear the stories of their faith but see them as well—especially those who could not read. By the dawning the third Century, Christians were beginning to express their faith in various forms of visual art. At first, the focus was on common symbols in the culture that could be endowed with a Christian significance—the dove, the fish, the chalice, the ship tossed by the waves, the anchor, and of course the cross.

It was then natural that frescoes of the common culture would be used, especially in the catacombs, depicting comforting images of the afterlife. The orans figure of prayer, the peacock and garden scenes, images of the queen of heaven, and the humanitarian image of a shepherd carrying a sheep on his shoulders, were all baptized with a Christian interpretation.

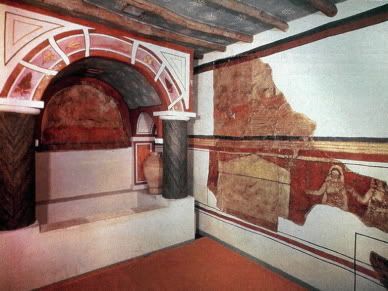

It was natural to add to those images, scenes of Old Testament stories, and followed quickly by stories from the Gospels. The earliest known example of a church with such pictures is the house at Dura on the Euphrates, adapted for use as a church in the year 232. It clearly followed the model of decoration found at the nearby synagogue at Dura, which depicted many biblical scenes.

Above, frescoes of Old Testament scenes at the synagogue of Dura.

Below, the baptistry of the house church at Dura with similar adornment.

With the legalization of Christianity under Constantine and the waning influence of the pagan cults, the Church no longer had cause to be as reticent in the visual expression of the faith. The cult of relics and imperial court ritual also lent influence to the treatment given to clergy, symbols, and images, all now being honored with lights and incense.

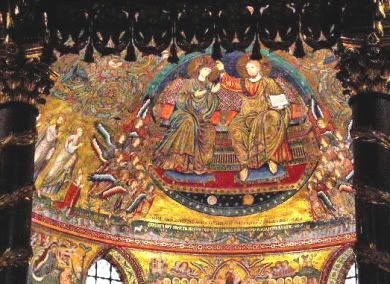

The defense of the full divinity of Christ in the first ecumenical councils, and the endorsement of the title of Theotokos for Mary at Ephesus gave further incentive for new images of Christ and the saints. And the depiction of Mary in the mosaics of St Mary Major in Rome, built after the council of Ephesus (431) is important in showing the development of now honoring Mary and the saints in their own right—not just as part of the background of the gospel story. It became the popular norm.

Yet the old puritan strain never completely died out. These depictions of Christ and the saints caused pain for those who cherished the memory of an older austerity and reserve, especially when they saw crude nickknacks in the marketplace. (Perhaps the tacky plastic glow-in-the-dark statues of Our Lady and the infant of Prague come to mind. Let the reader understand.) We might say that the intelligentsia lagged behind the devotional sense of the laity. And so it was that these images became the object of an undercurrent of mistrust and hostility that erupted into the iconoclastic controversy of the eighth Century.

In comparison with the West, the Eastern Church was always noted for the degree of its subjection to the authority and the whims of the emperors. Which is to say that imperial policy and involvement is a great factor in the doctrinal story of the Byzantine Church. By this time, the Byzantine empire had been through a period of decline. The Moslem conquests, Bulgarian invasions, and a series of inept emperors seemed to confirm that Byzantium was at en end. But when the Isaurian dynasty ascended to power with Emporer Leo III in the year 717, it seemed if there might indeed be new life and stability for the old empire.

Leo set about a vast program of badly needed imperial reform and restoration. His government organized the bureaucracy, revised laws, build roads, sponsored schools, and fended off the Arabs and Bulgars. All of this went over rather well, except for the religious policy of iconoclasm—the destruction of Christian images. The reasons for the new policy were complex, and in hindsight perplexing.

Constantinople certainly wanted peace with Moslems, Jews and Christian Monophysites—all of whom were opposed to religious images. It was also probably an attempt to curb the influence of monasteries. But even more, it is clear that Leo believed that the cult of images in his day was a form of idolatry that had crept into the church—especially the superstitions in the cult of icons among the unlearned laity.

In Leo’s mind, not only was iconoclasm the most needed reform in the church, as the emporer, he was the one responsible for reforming it. And so it began in 725 when Leo ordered the destruction of an icon of Christ, to which miraculous powers had been attributed. His edict was vigorously opposed in the East and simply ignored in the West.

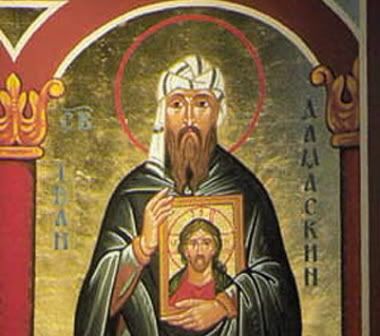

One of those who opposed the edict was the Patriarch of Constantinople at the time named German. So Leo simply had him deposed and replaced. Into this controversy come a powerful mother and an old monk name John. John was born in the year 676 in Damascus, Syria, which had by this time become the capital of the Moslem Umayyad Empire which stretched from Spain to India.

John’s father, though an important official in the court of the Caliph, was a Christian, and a very generous and righteous man. As he had done for many others, John’s father paid the ransom for a monk named Cosmas, enslaved by the Moslems. Out of gratitude, Cosmas schooled John in Christian thinking and learning, training his as a scholar.

John succeeded his father at the court of the Caliph, but was not satisfied and left after three years to become a monk and priest at St Sabas, Jerusalem. There, he labored long and hard in the patient work of theology and liturgy, becoming one of the greatest hymnist of the East, as well as the last of the early Church Fathers and the first of the medieval scholastics.

Securely in the Eastern theological tradition, John wrote apologetic works expounding and defending the faith in response to the Moslems, as well as the Manichees, the Nestorians, and the Monophysites. He eventually composed the first attempt at a systematic theology in the Eastern Church, his Source of Knowledge.

Iconoclastic Emporers Leo III (left) and his son Constantine V (right).

When the iconoclastic controversy erupted, John like many others, vigorously opposed the edict and wrote in defense of images. By living outside the empire, John had the advantage of some protection from Leo III and his successor Constantine V, who continued the iconoclastic policy of his father. But he was still in danger.

The emperor once planted a forged letter in which John offered to surrender Damascus to the Byzantines, so the Calif cut off the saint’s right hand. Naturally, the devout John went into the church and stood before an icon of Mary, imploring the Virgin’s intercession. Perhaps because he would write in defense of icons, it is said his hand was miraculously restored.

John was known for great humility, quietly receiving the mockery of others when he returned to Damascus as a monk to sell his woven baskets. After all, he once collected their taxes, and now it was time for payback. He was called John of golden streams because of his eloquence. He was a man of deep learning and simple piety, who spoke in a way that people could understand.

John Damascene succeeded in that labor where others had failed because of his deep sense of the reality of the incarnation, of Jesus as God and Man. For him, the controversy over icons, touched upon so many of the central truths of the Catholic faith, and he was able to articulate that better than anyone else. John fell asleep in the peace of Christ in the year 754 at the age of 78, but his labor for the gospel as the apostle of icons was yet to find its full effect.

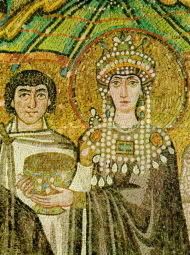

Emporer Leo’s son Constantine V, who had continued iconoclasm and even had a puppet council condemn images, died in 741, and his son Leo IV reigned briefly and died in 775. The new Emperor Constantine VI was merely a boy when his father died, so his mother Irene was made regent and Empress of Byzantium. Irene (meaning “peace”) loved the sacred images of the Christ and the saints.

She was pained by seeing them destroyed, by the turmoil in the Church, and by the persecution of the monks. Irene revoked the edict against images, appointed an iconodule named Tarasius as Patriarch of Constantinople, and with the help of Tarasius and Pope Hadrian I, summoned a Council at Nicaea in 787. That council defended the proper use of images in the Church and anathematized the iconoclasts.

There would be one further historical hiccup of iconoclastic emperors with a period of image-breaking and persecution until another female regent named Theodora would finally end the iconoclasm for good. Her name means “lover of God.” The Second Council of Nicaea was confirmed and the images restored on March 11, 842—an event still celebrated to this day throughout the Eastern Church on the First Sunday in Lent as the “Triumph of Orthodoxy.” And with Nicaea II, the orthodox, catholic expression of Christianity became “the Church of the Seven Councils.”

Two iconodule regents, Empress Irene (left) and Empress Theodora (right).

John of Damascus was highly praised at this last of the ecumenical councils of the undivided Christian Church of the first millennium. He had picked up on German of Constantinople’s original defense of images when iconoclasm broke out, and articulated it well. German and John explained how the so-called “worship” given to the images was different in kind from the worship of God, but also derived from it. Following their theological defense, the council defined that the images were to be restored and rightly honored.

The council stated:

“For the more frequently one contemplates these images, the more gladly he will be led to remember their prototypes, and the more will he be drawn to it and inclined to give it . . . a respectful veneration (proskynesis), but not however, the veritable worship (latria) which, according to our faith, belongs to God alone. But as is done for the image of the revered and life-giving cross and the holy gospels and other sacred objects, let an oblation of incense and lights be made to give honor to these images according to the pious custom of the ancients, for the honor given to an image passes over to its prototype, and whoever venerates an image venerates in it the person represented.”

The iconoclastic theologians has argued that the divine nature could not be circumscribed, and when one tries to depict Christ in his human nature, he depicts either a divided Nestorian Christ or a Monophysite Christ. But for John, it was all a thinly veiled revival of Manichean dualism. If John were writing after the invention of photography, he would have said, "Look, if one can take a picture of Christ, one can paint a picture of Christ." The fact that the divine Word did indeed become flesh is tremendously important. For St John Damascene, matter truly matters.

In his First Apology for Images, he wrote:

“In former times, God, who is without form or body, could never be depicted. But now, when God is seen in the flesh conversing with men, I make an image of the God whom I see. I do not worship matter; I worship the Creator of matter, who became matter for my sake; who willed to make his abode in matter; who worked out my salvation through matter. Never will I cease honoring the matter which wrought my salvation! I honor it, but not as God. . . . God’s body is God because it is joined to his person by a union which shall never pass away. The divine nature remains the same; the flesh created in time is quickened by a soul endowed with reason. Because of this, I salute all the rest of mater with reverence, because God has filled it with his grace and power. . . . Do not despise matter, for it is not despicable; nothing God has made is despicable.”

There is one true image of God. Speaking of Jesus in Colossians 1:15, St Paul wrote, “He is the ikon of the invisible God.” As his brothers, sharing his priesthood, you are images of Christ. As the old saying goes, Sacerdos alter Christus (“the priest is another Christ.”) That is, by the grace of holy orders, the Christian priest is indelibly and metaphysically conformed to Christ--the ultimate source and irreplaceable model of all priesthood. Jesus’ will that the apostles “do this as my memorial” requires that they stand in his place and speak his words (i.e., not “this is his Body”, but “this is my Body.”)

You are an icon of Jesus Christ, written by the Holy Spirit himself. We are images of the priest who has entered the veil of heaven and offered his own blood as an atonement for the sins of the people.

The Rule of the Priestly Society of the Holy Cross states:

“3. The call of Christ invites us to take up the Cross, and to follow in the way of the Cross, in faithfulness and obedience to Christ, and in union with him, even to death, and beyond death. The Brethren shall therefore endeavor to live out the discipline of the Crucified Saviour in every aspect of life, and, through their teaching and pastoral care, to help others to do the same.”

The Christian presbyter is the icon of Christ as both the Priest and the Victim in the act of worship we have come to know as the Holy Eucharist. Let us examine ourselves anew in the light of our great High Priest. How clear is that image of Christ in you and in your life? Is he visible in you? Can they see the wounds?—on you head, in your hands, in your side? Can they see in you the teacher? the healer? the good shepherd?

Do they love you (venerate you) because of your power? your stature? your charm? your way with words? your new Gamerelli cassock? Or is it because they see in you, him whom they love above all? When you find that image, do not destroy it; display it and defend it as did St John of Damascus.

Let us pray.

Almighty and everlasting God, who for the defense of the honor of holy images didst endue thy blessed Saint John with heavenly learning and wondrous strength of spirit: grant unto us, we pray thee, that by his intercession and example, we may so honor the images of thy saints, that we may follow them in all true godliness, and feel the effectual succor of their advocacy; through Jesus Christ our Lord. Amen.

This isn't really a homily, is it? It's more a history lesson, isn't it? A very fine history lesson, indeed. But, I'm curious: how do you count this a homily?

ReplyDeleteIt has a lot of history and hagiography, but it really is a homily (though thematic this time, rather than my normal expository style). The history lesson leads to a proclamation of the gospel and a call for the audience to renew its commitment and apply the lesson to their lives (in this case, to be true icons of Jesus in their ministry).

ReplyDeleteI should also note that I'm not differentiating between homily and sermon here. If I were, I'd describe this more as a sermon.

It might also make more sense if I added that the "audience" here were all priests of the Society of the Holy Cross.

ReplyDeleteAh, that makes tons of sense. As any reader of the inconsistencies of the Pauline letters will attest, audience makes all the difference.

ReplyDeleteAnd yes, this is a sermon, rather than a homily.

BTW, I've tried responding to this for a few days now. I suspect my resistence to opening a 'google account' is the blame.

I've just now opened one. If this prints, we shall know the culprit.

I know, I've had some trouble like that when everything was switching over. I'm still not used to signing in differently.

ReplyDelete