Several people have asked me to post this sermon (Epiphany I, Year A) I recently preached at St Alban's, Arlington TX. The text is below. Click here to listen online.

Several people have asked me to post this sermon (Epiphany I, Year A) I recently preached at St Alban's, Arlington TX. The text is below. Click here to listen online.Epiphany is about revelations and discoveries; it is about manifestations and unveilings; it is about vision and understanding.

On the feast of Epiphany, the magi have arrived to offer their royal gifts of gold, frankincense and myrrh to the newborn king. The holy family has none of the trappings of royalty, but it is by the sign of a heavenly light, and their discernment possible through inner light, that they see the hidden glory of the Christ child by faith.

That glory is next witnessed when it is manifested at the Baptism of our Lord, which we commemorate on the first Sunday after the Epiphany. John the Baptist was preaching and baptizing in the wilderness of Judea. The crowds came to hear his strong rebuke of their sins. He cried,

“Repent, for the kingdom of heaven is at hand!” He in strong terms, but he was also one who spoke to the heart. He named names, and humbly called others into accountability. When the people heard this, many were moved by God’s spirit and convicted of their sinfulness and their need for God’s mercy. By droves, they came down into the Jordan river to be baptized. This was the river that Joshua had led the people of Israel to cross when entering into the Promised Land. It was a way of beginning again.

The Jewish tradition has many forms of ritual washings. Baptism for the Jews was a washing of ritual conversion. John the Baptist said this washing was also to be a baptism of repentance. In Hebrew, repentance means to turn around and go the opposite direction. In Greek, it means to change your mind in a profound way. Repentance is the kind of change that leads to a whole new outlook on life, and a new way of living.

To walk down into the Jordan river to be baptized meant that someone was saying,

"It is time for my life to be turned around. I see the sin that clings to my soul, and it is time to change. I want to come back to God. I have had an Epiphany—a clear vision of how I look in God’s light. And I can see that I am in need of God’s mercy. I am coming to say that I need to be washed clean. I need to be made pure. I need God’s mercies poured out like a river."And one day, Jesus is among them. John’s message is very similar to the message Jesus will preach—

“Repent, for the kingdom of God is at hand.” We would not be at all surprised to see Jesus among the crowd—ministering to their needs, encouraging others to turn to God for mercy.

But Jesus does more. He walks down into the river. Jesus goes up to John to be baptized. John is astonished. He knows that Jesus is truly righteous in God’s sight. Jesus has no need to turn his life around. Jesus has no need of repentance. His entire will has been submitted to his heavenly Father. We are even told that John deliberately tried to stop him. He says to Jesus, “I’m the one who should be baptized by you. And yet you come to be baptized by me?” Jesus doesn’t try to explain it all or make him understand; he simply asks for an exception. Jesus says,

“It is fitting. You may not understand it now, but it is the right thing to do. It is fitting for us to fulfill all righteousness."What John and others would come to discover is that it is through Jesus’ baptism that this ritual was to become the way of righteousness. Jesus would later tell Nicodemus, in a moment of tender counsel,

“You must be born again. . . . Very truly I tell you, unless you are born of water and the Spirit, you cannot enter the kingdom of God.”In a spirit of humble obedience, John baptized Jesus. The heavens were open, and God manifested his will for redemption. The Holy Spirit descended upon Jesus in bodily form—as a dove. The voice of the Father came from heaven: “This is my beloved Son”

In this, Jesus was anointed as the Messiah, was commissioned in his earthly ministry, and was revealed to be the redeemer of the world. This was the final divine wonder revealing redemption through water, foreshadowing the institution we know as baptism. Jesus transformed ordinary things and common rituals by making them sacramental vehicles of God’s grace and inner transformation. Jesus took a ceremonial washing, anointing with oil, the laying on of hands, and a meal of bread and wine and transformed them into signs of God's power at work in us.

The baptism of John was not the same as the sacrament of baptism we know now in the Church. The baptism of John was a ritual washing—a sign of repentance, but there was no transformation by the Holy Spirit. The people would come to be baptized as a public sign to show their desire to be clean and holy before God. Jesus sanctified John’s baptism of repentance (he "baptized baptism"), making it a

"washing of regeneration and renewal by the Holy Spirit," according to St Paul’s letter to Titus.

It is through the water of Christ’s institution of Holy Baptism that we partake of Christ’s burial and resurrection, and are reborn through the Holy Spirit. Baptism acts a symbol of death and rebirth. St Peter compares baptism to the floodwaters who

“were saved through water” (1 Pet 3:20). Of course, the floodwaters are what drowned the wicked people of the world,

The Greek word for baptize (

baptizo), means to immerse or plunge, the same word used to describe the sinking of a ship. It is through being let down into the water that we

“were buried with him in baptism . . . so that as Christ was raised from the dead by the glory of the Father, we too might walk in newness of life” (Col 2:12)

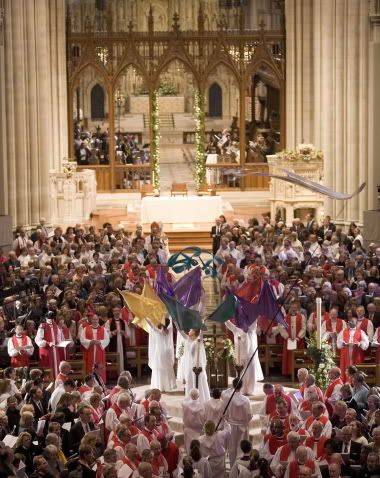

This new life, a new beginning comes when our sins are washed away and we become an adopted child of God, part of God’s family. The baptized Christian is united to Jesus as the head of the Church. This incorporation means that we are made a part of the Mystical Body of Christ, which is his holy Catholic Church.

St Paul captured this type of community by writing,

“We, who are many, are one body in Christ, and individually we are members of one another.” He also wrote,

“You were washed, you were sanctified, you were justified in the name of the Lord Jesus Christ and in the Spirit of our God.” No matter how disastrous the life of sin may have been, this is remitted in baptism. Isaiah says

“Though your sins be as scarlet, they shall be as white as snow.” The soul is purified by grace and given the righteous merits of Christ. St Jerome said,

“All sins are forgiven in baptism.”While all of the guilt of sin is washed away in baptism, that does not mean that when we look back at the mistakes we have made in the past, we will not feel guilty. The good news is that those feelings of guilt are counterbalanced with the faith that Jesus has takes those sins to the cross.

A person must come to Christ in faith and repentance to be baptized, for he alone is the gateway to eternal life. One must deny himself and any trust in his own merits, trusting instead in the merits and atonement of our Lord and Savior Jesus Christ. At such point, he is ready to be baptized, to exist “in Christ.”

So often, we tend to see baptism as the end of the conversion rode for adults. We expend all our energy trying to get them to come to church, to convince them of the Christian gospel, to get them to commit to following Christ, and their baptism is the crowning celebration of our effort.

But this is not what baptism is all about. Baptism is not an

end to conversion, but a

beginning. It was at his baptism that Jesus

began his public ministry. The declaration of Jesus’ sonship from above was not the gold watch for a job well done, it was a description of Jesus’ role in the world, of how he would serve God and man as Son and Savior.

Living “in Christ,” as St Paul so often puts it, is to live in a baptismal life. It is a life of endless renewal. Jesus does not satisfy our temporary thirst; he puts in us a well from which spring up the waters of eternal life. God can take ordinary people like you and I and transform us. And he can make us agents of transformation for others in need of mercy. As he promised to the woman at the well, Jesus can give you that well of water on the inside, always springing up fresh waters of God’s graces.

Let us then resolve to turn to those waters and drink day by day. Let us commit ourselves anew to being active and faithful members of Christ’ mystical Body on earth—the Catholic Church. And let us encourage others to meet Jesus in the Jordan River. Amen.