I am currently reading through The Pilgrim: Pope Paul VI, the Council, & the Church in a Time of Decision by Dr. Malachi Martin (published after the second session of Vatican II in 1964 under the pseudonym Michael Serafian). I have come across many interesting passages so far. It is no secret that Martin, the traditionalist, was a revisionary liberal back in those days (as was Josef Ratzinger). Their liberalism, of course, was not without reason. I thought I would share one passage (pp 13-16) which described "what it was like," for those of us who were not there or did not know.

Much has been written and said of a denigratory nature about the Curial mentality, mainly by people who do not know what the Curia is. It is impossible it is said that the majority of these Churchmen are in bad faith and are not acting from true zeal. If the contrary were true, a normal law for the conduct of human relations would no longer hold true.

The truth and reality are quite different, and more ghastly. The majority of these men are convinced "conservatives." There is no question of bad faith or viciousness on their part. It is a question of human blindness and historical ignorance. The mentality is somewhat as follows: As regards the Church: The Church consisting of Pope, Curia, bishops and religious orders, is there be divine appointment to take care of the people who belong to the Church. The Vatican Congregations, especially the Holy Office, are the organs of the Holy Father, and they share, therefore, his infallibility. The pillars of this Church are her universal canon law, her universal language—Latin. Since the first Vatican Council (1869) there is no further need for ecumenical councils; the Pope can decide for himself what is best for the Church. Collegiality is not based either on Scripture or Tradition. As regards those who belong to other Christian denominations: they are in grave error; they have but one alternative, namely, to renounce their errors and return to the fold of Peter. Submission is the condition for admission. Humility precedes unity. As regards other religions in general, whether Christian or non-Christian, error has no rights, and the erring person is in an inferior position.

As regards the State: the ideal arrangement is a state which acknowledges the Roman Catholic Church as the true Church, a confessional state. In the concrete order, the Church must temporize, but her doctrine remains intact and inviolate. As regards the Jews: the latter were guilty of crucifying God, and God put a curse on them for all time. Their sufferings and misery through the ages are but a divine recompense for their initial error and refusal to accept Christianity. As regards the Bible: modern attempts to interpret it in the light of archaeology, the literature, the languages, the culture, the civilization, the psychology of ancient peoples are tendentious, false, and lead to error.

With a sheaf of such principles in hand, there would be no difficulty in condemning anyone who appeared to err. And a denial of a fair hearing or trial or, indeed, of any word but that of condemnation, is logical, can even be holy. The refusal to go halfway to meet non-Catholic Christian brethren can be absolutely justified: return and submission are first required. It would be absolutely obligatory to ally oneself with the traditional, right-wing political forces in any given county. The reason: the latter hold out hope of a return of the confessional state, and error must be combatted by all good means.

Finally, this Curial mentality would and does inevitably lead to a frozen historical ghetto outlook which promotes increasingly a sense of irrelevancy and indifferentism. The whole affair of religion just does not seem to matter or be relevant to a world trying to solve concrete problems and which has been offered such ill-adopted instruments for this purpose. There is, finally, a kind of aura of glory around the Vatican administrative centre, a mystique of history, a feeling of timelessness, of continuity with past generations of two thousand years, of immediate relationship to countless generations to corne. This is the glowing heart of romanismus.

We must remember that the all-important Congregations which we have been discussing (in addition to others) are the product of the Tridentine and post-Tridentine period; they were and are the answer of the juridical, Roman mind to the onslaughts of the Reformers; they are also, in part, the answer of the same mentality to the problem of grappling with the modern age ushered in by the Industrial Revolution of the 18th century. Thus, the Holy Office was founded on July 21, 1542 by Paul III, and its procedures have remained the same since that date. The Consistorial was founded in 1591 by Gregory XIV. The Council on August 2, 1564, by Pius IV, the Seminaries and Universities in 1588 by Sixtus V, the Extraordinary Affairs in 1793 by Pius VI. This last owed its origin to the Vatican's difficulties with Revolutionary France. The Propagation of the Faith was established in July 1568 by Pius V, the Oriental in 1862 by Pius IX (by detaching a section from the Propagation of the Faith). The Secretariat of State dates from the time of Martin V (1417-1431).

Small wonder that the traditions, customs, and mentality of these institutions have hardly changed and hardly befit the modern conditions of the Church. Originally Italianate in membership and outlook, they were and are also Romanist in the full sense of the void. "Qui pensiamo in secoli" is an oft-repeated phrase in the corridors and offices of the Roman dicasteries ("We think in terms of centuries"). The Eternal City.

We are here at grips with a true mystique, a group mentality that has never found adequate expression but which nevertheless is part of the very atmosphere in which Romans live, work and die. Rome overflows its Seven Hills, piling up layers of eternity ind of time on top of each other, still refusing to be identified with any one epoch or period or culture. It stands apart even from the bones, marrow, essence of the ecclesial group to whom Christ promised eternity in time, His Church. Indeed this Church, the living organism that weaves dry dogma, dusty scholarship, imperious clericalism, prescribed rites, institutionalized sanctity, sinners, saints, all into one pulsating living thing, the Church, is not seen in Rome, nor is the glowing centre of the Roman mentality. If Christ came back as He was two thousand years ago, He would not be at home here; He spoke no Latin; He did not wear satin slippers. And this is admitted by these Roman minds. No, the mystique is as much that of the Roman Emperors as of Roman bishops, as much the elegance of Roman Diana as the supernatural beauty ascribed to the Virgin. And when Greek hymns, Coptic songs, or Latin chants swell up beneath the spanning arch of the Roman basilica, it is impossible to hear the melodies of Moses and Miriam, the Voice of Yahweh on Sinai, or the gentle tones of the Sermon on the Mount. For Romanism is a human expression of an historical garb the Message has assumed. The essential lines of that garment are divinely ordained: Peter is to have successors in perpetuity, the priest is to consecrate, minister, the bishop to rule, the faith to be kept alive, the moral rule to be observed intact.

1 comment:

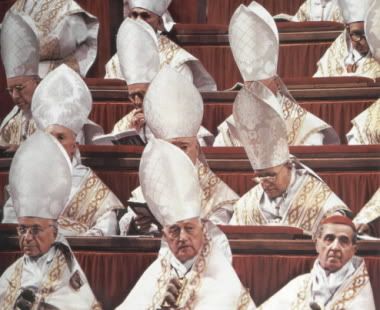

Thrilling headgear!

Post a Comment